This Week In Veloren 119

This week, we take a deep dive into the recent physics overhaul with @lboklin. We also see improvements in the moderations, translation, and skill systems.

- AngelOnFira, TWiV Editor

Contributor Work

Thanks to this week's contributors, @Sam, @Slipped, @xMAC94x, @juliancoffee, @Snowram, @Pfau, @Sharp, @zesterer, @aweinstock, @aws107, @nwildner, @James, @Danielduel, @imbris, and @Yusdacra!

At this week's meeting, we set a release date for 0.10 to be June 5th. We have had a ton of changes over the last few months, and we're excited to get a formal release together! We've also recently passed 1000 stars on both GitLab and GitHub!

This week, @Sam has been reworking clay golems. @Sharp fixed shadows in wgpu, which means that the last blocker to get it merged is OSX builds. Changes have also been made to improve how moderators have control over a server.

Moderation tools by @Sharp

I just finished up a decent-sized change that allows timed bans and non-administrator moderators (which involved a few updates to the security model). It also switches us to a versioned settings file for editable settings and migrates from the old format, so going forward we can add metadata and stuff to settings files without breaking backwards compatibility. This should be the precursor to nicer mod tool functionality.

Skills and translation diagnostics by @juliancoffee

I've added /skill_preset command which allows you to unlock pack of skills or reset your skillset to fresh character. Currently, there is only one 'max' preset which just instantly unlocks all skills and upgrades it to max level, but new presets can be added in 'assets/server/manifests/presets.ron'.

Also I created binary to run diagnostic of specific language for translators by extracting i18n code to its own crate. With no serious dependencies, it compiles very fast even from scratch and allows to get quick feedback on changes to localization. For anyone who uses the /spawn command I also have good news. I added auto-complete of species (before it was just body kind, like biped_large).

Updates by @aweinstock

I did the following this week:

- Added damage types (Piercing, Slashing, Crushing, Energy) to combat skills; Piercing attacks (such as arrows) now partially ignore armor damage resistance.

- Fixed an issue where projectiles would miss entities that had terrain too close behind them (primarily small things like squirrels from a downward angle, or cultists next to walls).

- Made merchants nametags visible at a higher distance, since players had difficulty finding merchants in towns.

- Added a pulsing red warning on the 2nd phase of a trade when one party is trading no items, since players were mistakenly giving merchants items for free.

New playable species by @Pfau

We discussed new playable species and came up with these things:

- The undead will get a visual overhaul to look more like Draugr from northern mythology (Don't worry, they will still look like undead!)

- The actual new species we will introduce over the course of the next months are:

- The Aunqa: Elemental/Geode style species with oriental features

- The Morx: Bird/Crow species with a Gothic/Steampunk/Pest-Doctor theme

(Screenshots coming whenever we got something to show off...)

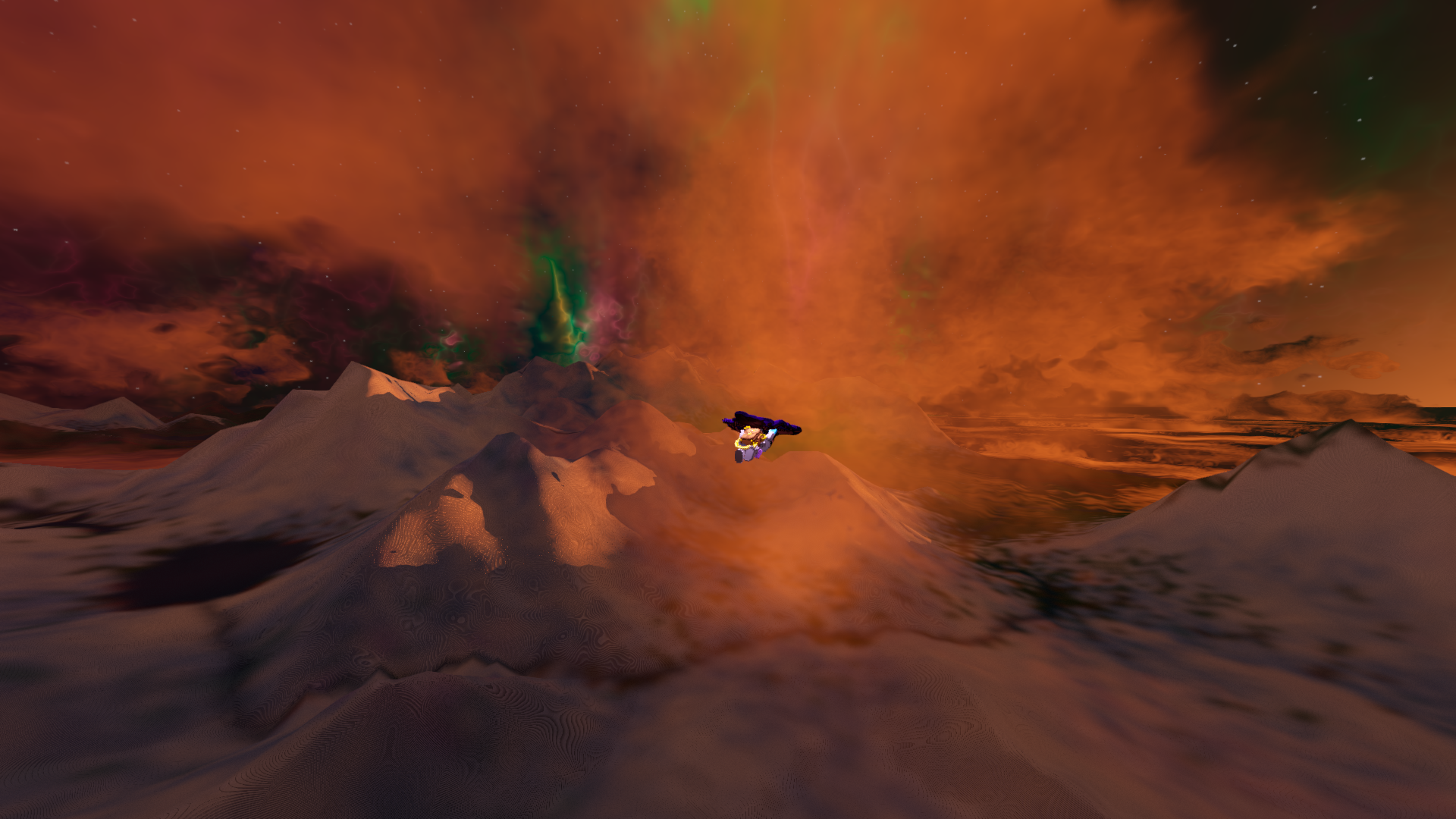

Implementing physics and then glider physics by @lboklin

Physics in Veloren has been a long road for me. It began some time after discovering the game late last year, when I decided the gliders could be more than they were. How hard could some basic aerodynamics simulation possibly be?

There were a couple of false starts, a lot of refactors and changes in approach. I submitted my first draft MR a few days before the end of last year. It began a bit rough, with a lot of little quirks since I didn't really understand what I was implementing and what I wasn't. I spent a good few weeks on controls alone. Finding an intuitive way to control 3D movement that gives justice to the complexity of the gliding mechanics was one of the hardest things, and making it look and feel right was even harder.

As time went on I kept coming up with complex solutions to complex issues. At some point I asked myself whether this one mechanic in the game justified implementing rigid body dynamics. I decided that even if it did, I didn't want to bother with it then, or I would never get anything done. I wanted to reduce the size and complexity of the MR, so I began splitting things out that wasn't directly related to the hardest part of glider physics, such as some much needed refactors, basic Newtonian physics, and equations for things like drag to replace the hacks that powered the old physics system.

So then I took some time off from working on gliding to get these prerequisite features and changes into the game. I managed one small MR before creating another monster that was the addition of masses, densities, basic implementation of buoyancy, and aerodynamic drag (with all the fluid types and relevant fluid dynamic equations). Admittedly, buoyancy didn't really have to be part of it, but it made contextual sense and so I added it anyway because I have no sense of priority.

These massive changes more or less fundamentally broke or changed the way every physical entity interacted with each other. Knockbacks now depended on mass and applied impulse strength; pushback from collisions made moving some things much less feasible while other things like campfires and turrets now slid around when pushed; projectiles used to have their own gravity to give them a custom arc which obviously wasn't very compatible, so that changed as well (which required implementing proper projectile motion prediction by enemies, which @James helped me with). And we haven't even gotten to the water and air interactions! If it weren't for @Ygor's endless testing and feedback I would still be fixing numerical mistakes and tweaking values to this day.

In addition to entities being assigned mass, I also gave them density. By giving entities a density I could then use that to derive buoyancy under the simplifying assumption that their mass is equally distributed over their height, so as they become submersed in water their effective weight is reduced based on the ratio of (toe) depth to their height. The gravity experienced by an entity is gravity * (density - fluid_density) / density, where fluid_density can be a mix of density of air and density of water if partially submersed.

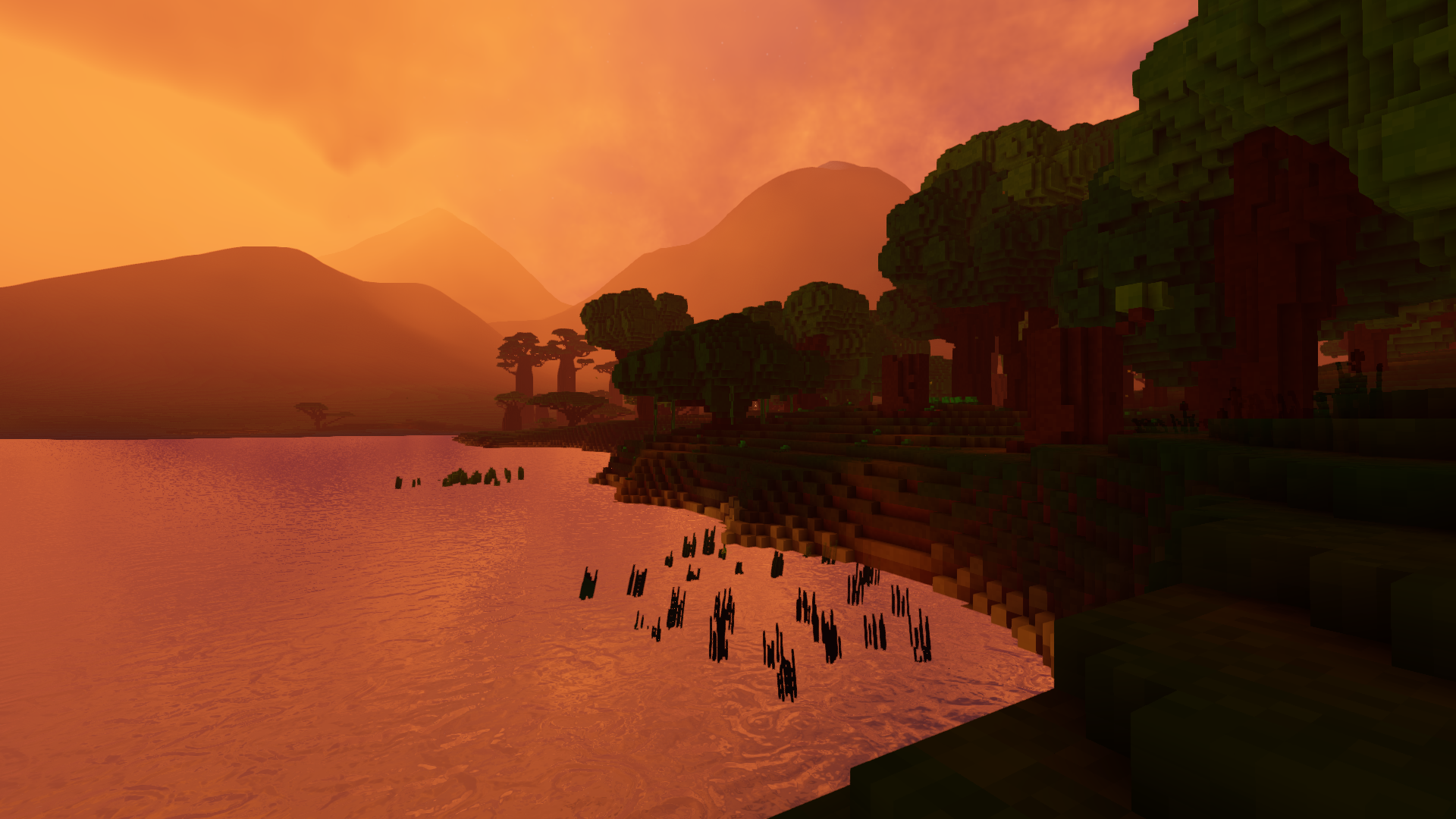

In the end, this allows things to float or sink based on this modifiable density component. As a proof of concept, I made airships control their elevation via modifying their density (which is the equivalent to pressure regulation in real life) and the capability for airships to become water ships by rapidly "deflating" their magical lighter-than-nothing balloon, leaving the ship with a density more or less equal to that of a normal 18th century sailing ship.

Now that entities had masses I also had to define some more accurate dimensions for entities (which had previously only been defined using height and radius) before I could begin to derive aerodynamic drag for them. Once everything had dimensions along each axis, it was time to implement the drag equation.

Aerodynamics, which is a subfield of gas dynamics and more generally fluid dynamics, are hard. It's one of the big unsolved problems in physics, and best we can do to make accurate predictions is through numerical methods, but we can't afford that in a game that isn't (just?) a flight simulator.

We have other things to simulate and compute, so running a full-blown fluid simulation for each and every entity in the game just to get precisely accurate aerodynamic behaviour is not anywhere on the table, unfortunately. Thus, my approach has been to find simplified models and analytical formulas with empirically derived coefficients as a substitute for fluid interactions we can't mathematically describe.

For each body type I had to define a drag coefficient, which is an arbitrary dimensionless constant which represents how approximately aerodynamic something is, and a reference area to complement it. The reference area is a number derived from the dimensions of an object in somewhat arbitrary ways, so that you can have two of the same type of shapes but of different sizes and have it affect the amount of drag affecting each.

Both the drag coefficient and reference area have to be looked up in scientific literature for each type of shape, and in many cases there is more than one convention used. For wings it is usually the planform (surface area of the wing as seen from above), for (ellipsoidal) airships it is the square of the cube root of its volume, and for spheres it is the projected circle area. Using the drag coefficient and reference area together with Bernoulli's equation gives us the total amount of drag produced by an entity in the direction opposite to their velocity (relative to wind, specifically, but wind velocity is currently invariably zero).

The above was the foundation I wanted in place before getting to the juicy part: aerodynamic lift. In comparison to lift, drag is quite easy: it's just drag_coefficient * reference_area * 0.5 * fluid_density * relative_flow_velocity² applied as a force in the direction of relative_flow_velocity. The formula for lift looks the same at this level of abstraction: lift_coefficient * reference_area * 0.5 * fluid_density * relative_flow_velocity², but it's applied in a direction that isn't necessarily perpendicular to either the wing's chord line (the line that goes from the leading edge to the trailing edge) nor perpendicular to the direction of flow.

This is because of an effect called downwash, which is due to vortices forming at the wingtips that pulls the wind along in a backwards and slightly downwards direction, producing a force called induced drag (aka drag due to lift), which shifts the lifting force vector rearwards. The angle between the lift and lift - induced_drag vectors is called the induced angle of attack and it can be derived from the lift coefficient and aspect ratio of the wing.

It's the lift coefficient that is the hard part. In my original attempt at implementing aerodynamic lift, I found this simple formula derived from something called the Thin Aerofoil Theory: it states that for an infinitely thin 2D aerofoil, the difference in lift over difference in angle of attack for small angles (up to ~15±3° depending on model) is simply 2π, and the section lift coefficient for the aerofoil is then 2πα, where α is angle of attack.

The section part of section lift coefficient is important, and something I struggled to reconcile with my goal at that point, because this 2D aerofoil is not only infinitely thin, but also has an infinite span. The significance of the infinite span is that it entirely removes spanwise flow (and thus wingtip vortices) from the equation, which means no induced drag. So what do we do when gliders most definitely have a finite span and glide around in 3D space?

I did not like the idea of deriving lift using this equation by simply multiplying the section lift coefficient by the number of aerofoil sections that would fit along the span the wing, partly because it just felt wrong and inappropriate, and partly because I had no solid understanding of what the actual consequences and trade-offs would be. Maybe it would be fun anyway.. maybe even more so than a correct model. Maybe it would feel a bit awkward but we never realise why or what we're missing out on. I didn't want that. To have players get used to erroneous behaviour and then maybe I (or someone else) comes back to fix these flaws and upsets everyone again in the name of some pesky realism and supposed correctness. So I went and borrowed a (really thick) book called Fundamentals of Aerodynamics (by John D. Anderson) and spent some time trying to learn and understand what was missing and to find out what I needed in order to simulate lift for a finite, 3-dimensional wing.

The book was very helpful, and also conveniently spoon-fed me with some useful analytical formulas I could apply with the caveats of them only applying to specific types of wings at limited ranges of angles of attack etc etc. In the end I went with the most straight forward approach with the simplest solution for finite, 3-dimensional wings that also accounts for induced drag: by simplifying every wing shape to be perfectly elliptical, parameterised only by span length and chord length.

With this simplification, we have a few equations that each handle slightly different cases for increased accuracy. For higher aspect ratio we have an equation derived from Prandtl's Lifting-line Theory. For lower aspect ratios we have a modification to that equation by H. B. Helmbold. For swept wings (which we aren't currently using) we use Küchemann's modification to the latter. The end result is what you can see right now on the live server (to the dismay of some players who really liked the old hover-gliders).

The biggest caveat right now that I'm not entirely happy with but see no good solution to (which is not to say there isn't one!) is that I don't know what to do with lateral wind. The equations simply don't account for side-slip (or yawed orientations), because the shape of the wing is then effectively skewed from the perspective of the oncoming wind, which changes the effective aspect ratio, spanwise flow and vortices at each wingtip, which consequently affects the induced drag and angular momentum in general.

Speaking of angular momentum: it's the trickiest part of rigid body dynamics by far, and is the reason I decided to forego that route in favour of simpler solutions to glider handling. That is to say we don't calculate the angular forces at all for either glider or pilot, so the lift and drag forces do not change the orientation of either. The character pendulum effects are a complete hack. This is why it's even more unfortunate that lateral wind is ignored since it ought to have a noticeable effect on the glider's rotation.

Aside from the issue of lateral wind, I would say the controls are the weakest point of the glider right now. It's something I'm currently trying to improve by removing the assumptions about what's up and what's down to allow freer maneuvers like loops and fully controlled rolls. I'm also not happy about the magical yawing, so I'm trying to work with roll and pitch exclusively. The heuristics for when and how to pitch and roll is turning out to be quite tricky, so we'll how that goes.

In the future I would like to implement different wing shapes. Tapered wings should be quite feasible as the equations wouldn't need much modification to account for it. Delta wings I'm not so sure about, but it's not out of the realm of possibility. On the less physics-heavy side of things I would also like to see gliders having individual dimensions (and shapes in the future; hopefully we'll see more aerodynamically shaped glider models too).

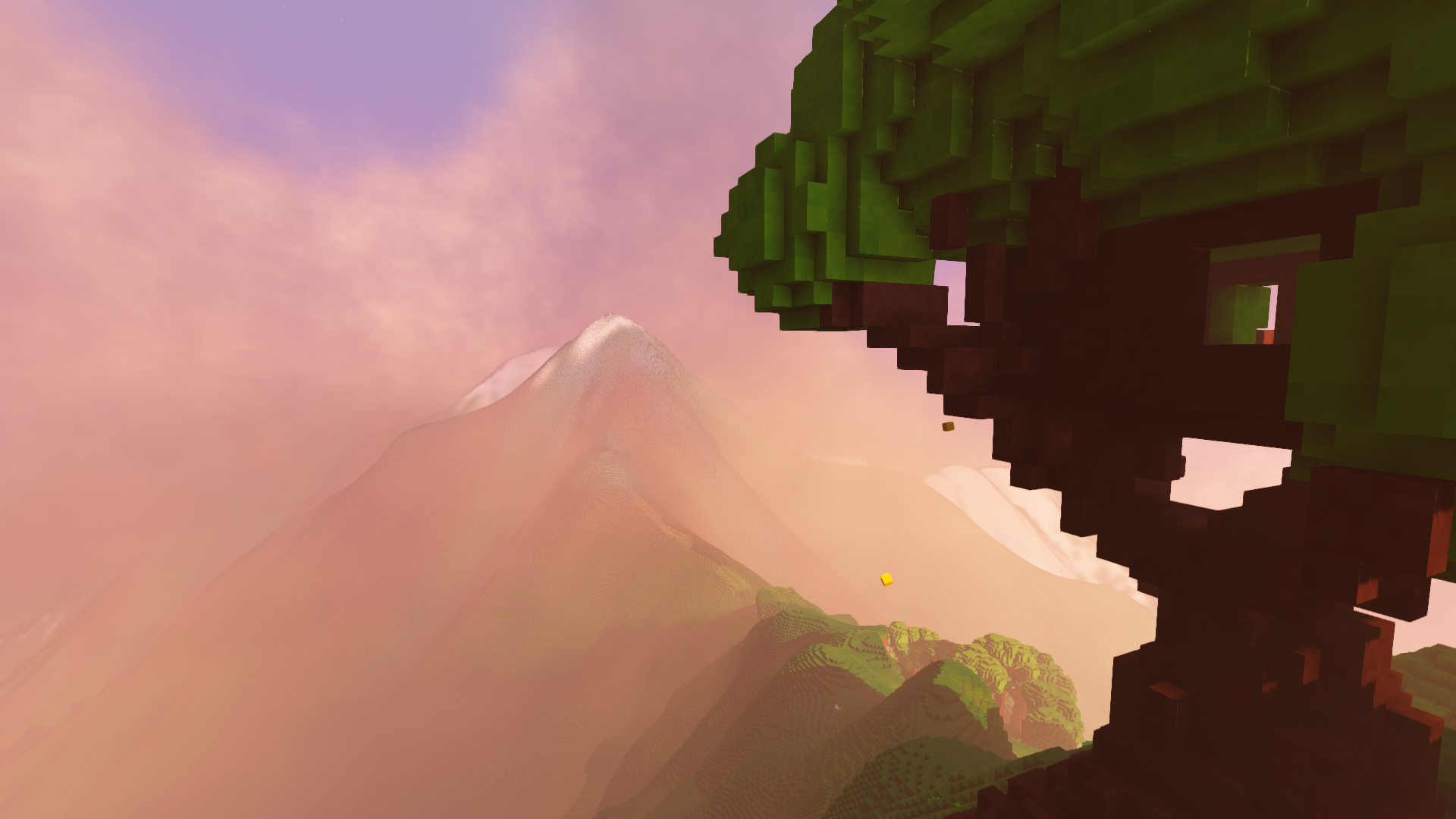

I also hope to have something to share on the topic of wind in the near future, but this is all for now. Two explorers, ready to set out on a quest. See you next week!