This Week In Veloren 32

Thanks to all of the contributors this week, @Desttinghim, @imbris, @scott-c, @haslersn, @andymac, @Slipped, @xMAC94x, @AngelOnFira, @Pfau, @Timo, @Geno, and @Zesterer!

The Future of Veloren by @Zesterer

Veloren started life as a Cube World clone. We make no secret about this, and it's very clear that Cube World is Veloren's primary influence. If you were to take a peek at the git history of the engine, you will find that, fittingly, 'Clone World' was the preliminary name we used for the project.

Times, however, have changed. Throughout Veloren's development, it has become clear to us that there are many aspects of Cube World that we feel dissatisfied with, and that there are many ideas we'd like to experiment with that Cube World does not explore.

Last week, the developer of Cube World, Wollay, broke his silence to announce a new Cube World release. Being fans of Cube World, we're all excited to play it - I'm sure it'll halt Veloren's development for at least a few days while we enjoy it.

Many have asked whether Cube World's imminent release will mean the end for Veloren. For us, without a shadow of a doubt, the answer is a decisive "no". Be it the community we've grown, the things we've learned, the artwork we've created, the engine we've built, or the ideas we've shared - it's clear to us that the potential for this project is unbounded.

That said, it's become clear to us that Veloren needs a stronger vision. It's not uncommon for us to find ourselves explaining what Veloren isn't rather than what it is. This partly stems from Veloren's origins as a clone, but it also stems from our open-ended development model. As of yet, we've avoiding planning more than one release ahead. In short, we've lacked a long-term vision for Veloren.

Starting this week, we intend to change that.

Throughout the next fortnight, we'll be looking to the future to plan a long-term roadmap for the project. We'll be talking to the community to gather as many ideas as possible, then we'll assemble them into a long-term plan that takes us from where we are now to a 1.0 release. That's not to say that this roadmap will be set in stone - as a community-driven project, new ideas will inevitably come along to replace old ones. However, this roadmap will provide us with the long-term vision we need to drive this project forward with purpose and clarity.

Development

Contributor work

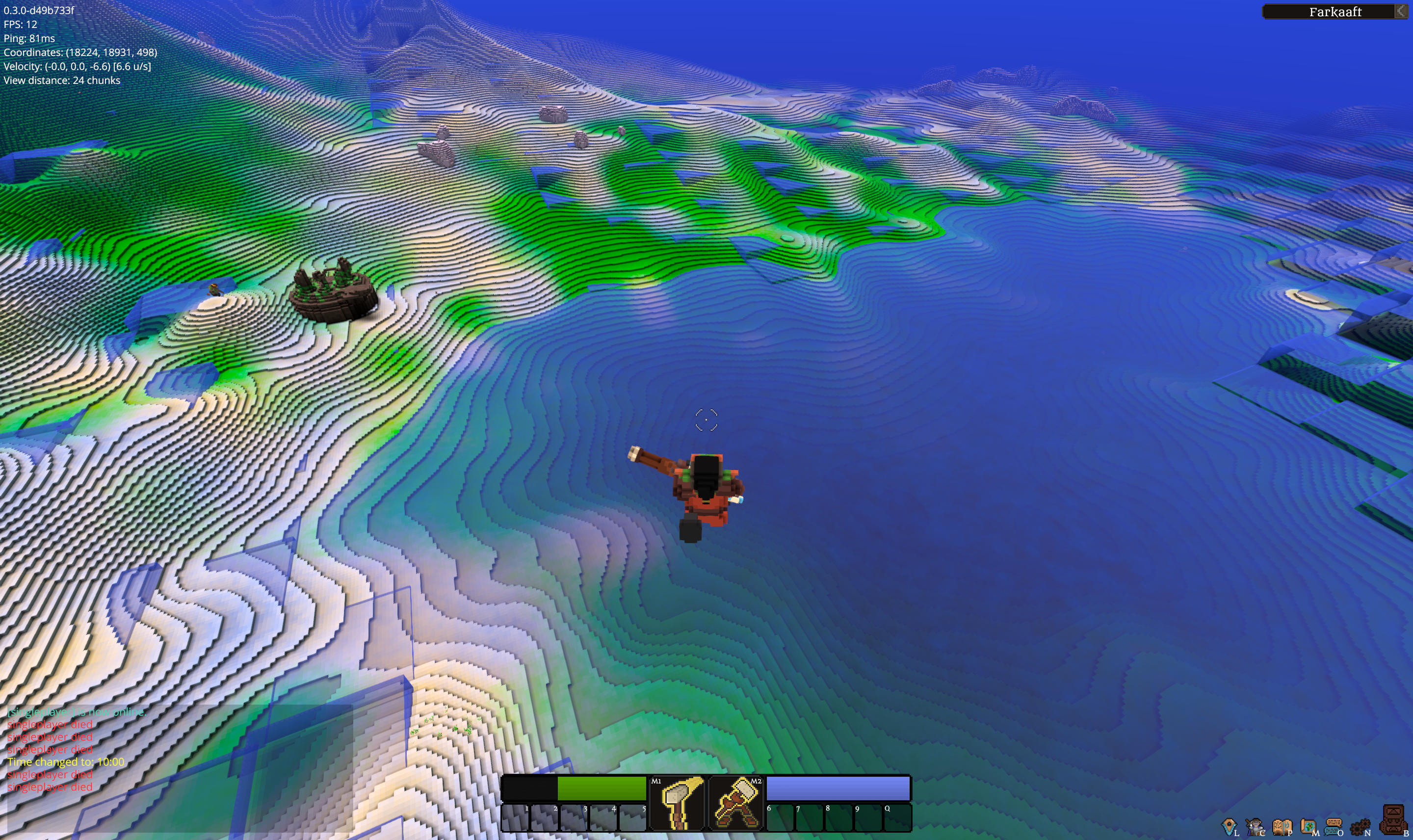

@Sharp has been continuing work on lakes and rivers. There is a lot to fiddle around with to make them feel natural. @Xacrimon has been continuing work on the authentication side and has just started working on account management. @Yurimomo has worked on improving the way we go about testing, and how we can improve our changelog. The debug work on the river systems

New Chunk Data Structure @haslersn

This week, @haslersn implemented a new chunk data structure. A chunk in Veloren is an arrangement of voxels which has an area of 32 by 32 voxels and is 16 voxels in height. All of the terrain is stored in a three-dimensional regular grid of such chunks. This holds true for both the old and the new data structure, both of which we'll now explain.

Previously, there were three types of chunks. The first type was a chunk that only contains copies of one voxel. This type was for example used if the chunk consisted solely of air. The second type was a chunk that mostly contains copies of one default voxel but is also sparsely filled with different voxels. Those deviations from the default voxel were stored in a hash table. The motivation for storing only the deviations was to save memory. The third type was a chunk that contains arbitrary voxels, stored in an array of length 32 x 32 x 16. This type was used if the second type couldn't save a considerable amount of memory anymore, because of too many deviations from the default. The first documented waterfall in Veloren!

However, the previous implementation wasn't very efficient because of two reasons. First, for every access to some voxel data there's a branch checking for the chunk type. Second, if the accessed chunk is of the second type and therefore uses a hash table, then a hash has to be calculated.

People tend to agree that the second reason is indeed a problem. For the first reason this less clear-cut. One might argue that consecutive accesses most often access the same chunk and then the branch predictor is right most of the time. We can't know without benchmarking and so we did. Before showing the benchmarking results, we explain the new data structure which gets along without a hash table.

In the new data structure, the chunk of 32 x 32 x 16 voxels is furthermore subdivided into groups of 4 x 4 x 4 voxels. Consequently, there are 256 such groups per chunk. Again, for every chunk, there's a default voxel. If within a group every voxel is a copy of that default voxel, then we don't store that group. If, on the other hand, a single voxel within a group deviates from the default voxel, then the whole group is stored. To store those groups, we have an array of voxels that grows dynamically every time a new group has to be stored. To track if a group is stored and wherein the voxel array it is stored, we have an extra index buffer that contains per group an index into the voxel array. Still to work to do on town generation!

In comparison to the old data structure, we get a little bit of memory overhead for empty or almost empty chunks, because we always store the index buffer. But in other cases where most voxel groups are filled with non-air voxels, we win in this respect.

We benchmarked old versus new, considering an arrangement of five stacked chunks that are filled with voxels, and obtained the following results.

| Benchmark | Old data structure | New data structure |

| ---------------------------------------- | -------------------|--------------------- |

| full read (81920 voxels) | 17.7ns per voxel | 3.6ns per voxel |

| constrained read (4913 voxels) | 67.0ns per voxel | 14.1ns per voxel |

| local read (125 voxels) | 17.5ns per voxel | 3.8ns per voxel |

| X-direction read (17 voxels) | 17.8ns per voxel | 4.2ns per voxel |

| Y-direction read (17 voxels) | 18.4ns per voxel | 4.5ns per voxel |

| Z-direction read (17 voxels) | 18.6ns per voxel | 5.4ns per voxel |

| long Z-direction read (65 voxels) | 18.0ns per voxel | 5.1ns per voxel |

| full write (dense) (81920 voxels) | 17.9ns per voxel | 12.4ns per voxel |

As you can see, the old data structure is defeated. Since we only considered completely filled chunks, the only seeming problem with the old data structure that could lead to this defeat was the extra branch. However, it's important to note that we can't be sure that this was the only reason why the old implementation performed worse. For sparsely filled chunks we assume an even greater improvement because hash tables are known to have slower access times than arrays, especially for the sizes relevant here.

Map and Minimap by @haslersn

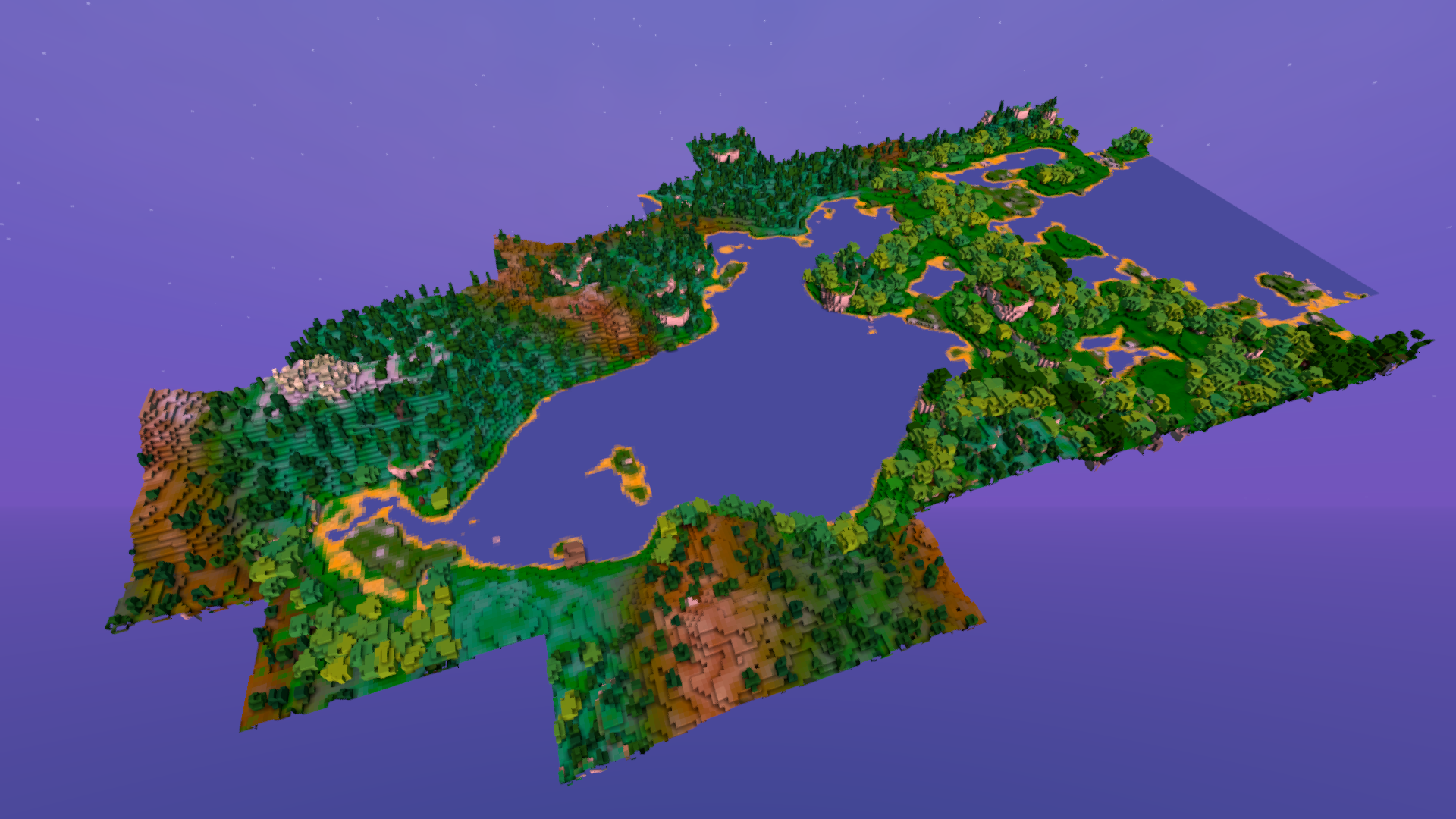

@haslersn also did some work on adding a map and mini-map. This is not yet merged into master, but a feature branch and several screenshots have been shared. The new minimap view!

As you can see, the map is three-dimensional and encompasses all of the structures which are present in the world. This is achieved by simply taking the actual terrain's voxel data and averaging a cube of 4 x 4 x 4 voxels into a single voxel on the map. Hereby the algorithm must consider only voxels that have, on any of the six squares, an adjacent air-voxel. Otherwise, a green pasture wouldn't look as green because not so green voxels from below the ground would be considered.

Implementation-wise, various additional code had to be added: Changes in the terrain need to trigger a generation or regeneration of the corresponding map chunk, map chunks need to be meshed and, of course, the minimap has to be rendered. If you pay close attention, you can see the player's figure on the minimap in one of the screenshots. Luckily the rendering code for the main scene could simply be re-used with some things disabled, so as to render the minimap and the desired figures thereon. Hence the main work was not to implement new code, but rather to adapt existing code to be re-usable in other contexts, such as for the minimap. This work is still ongoing. The real map and the player visible in the minimap. See you next week!