This Week In Veloren 43

This week we get a postmortem from @Sharp about their learnings on erosions to generate rivers and better land features. Also more on the CI improvements, a new article on dtf.ru, and other updates.

Contributor Work

Thanks to this week's contributors, @Zesterer and @xMAC94x, @Pfau, @Songtronix, @Slipped, @shandley, @telastrus!

This week, @xMAC94 and @AngelOnFira have been working on upgrades to CI. @xMAC94x worked primarily on improving the current CI by building the base image more frequently. @AngelOnFira focused on experiments with new CI setups on GitHub Actions, and some more OSXCross for Mac builds. @Songtronix got the FreeBSD build to compile again. They also worked on improving logging.

@RonVal4 and @DoNeo wrote a Veloren article on dtf.ru. It's worth a translated read if your Russian isn't очень хорошо! The game design group met up last Saturday to discuss non-damaging conditions in-game. They will be meeting again this Saturday to finish up this topic.

@chrischrischris will be continuing their work on advanced pathfinding for agents. Screenshots coming up in future devblogs! @imbris has been working on a bug where entities aren't properly sent to the client. The bug occurs when entities leave the visible range from the player and come back in. @imbris is close to solving the issue, but there are still some anomalies.

@Felixader has another Imgur gallery with some work they've been doing this week. @shandley has been continuing work on SFX.

River postmortem by @Sharp

After having done a lot on river, erosion, and world generation, @Sharp takes some time to dive into some ideas.

Nobody has ever been able to figure out a way to make river networks that fit the terrain with pure noise. The original authors of ideas like Perlin Noise were explicitly trying to find ways to reproduce geological features without running expensive simulations. These simulations would have been impractical for the time when they were working on these ideas many years ago.

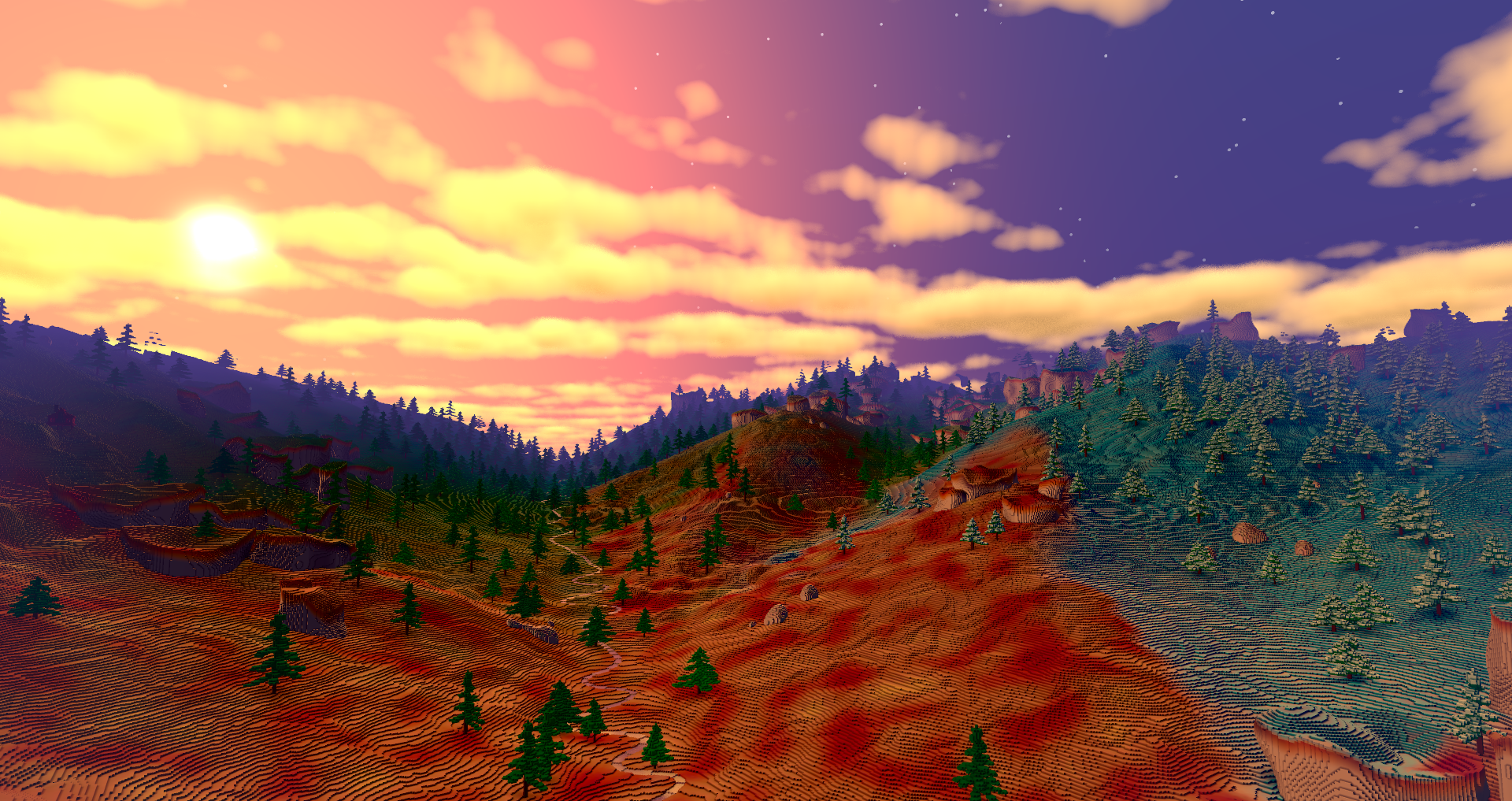

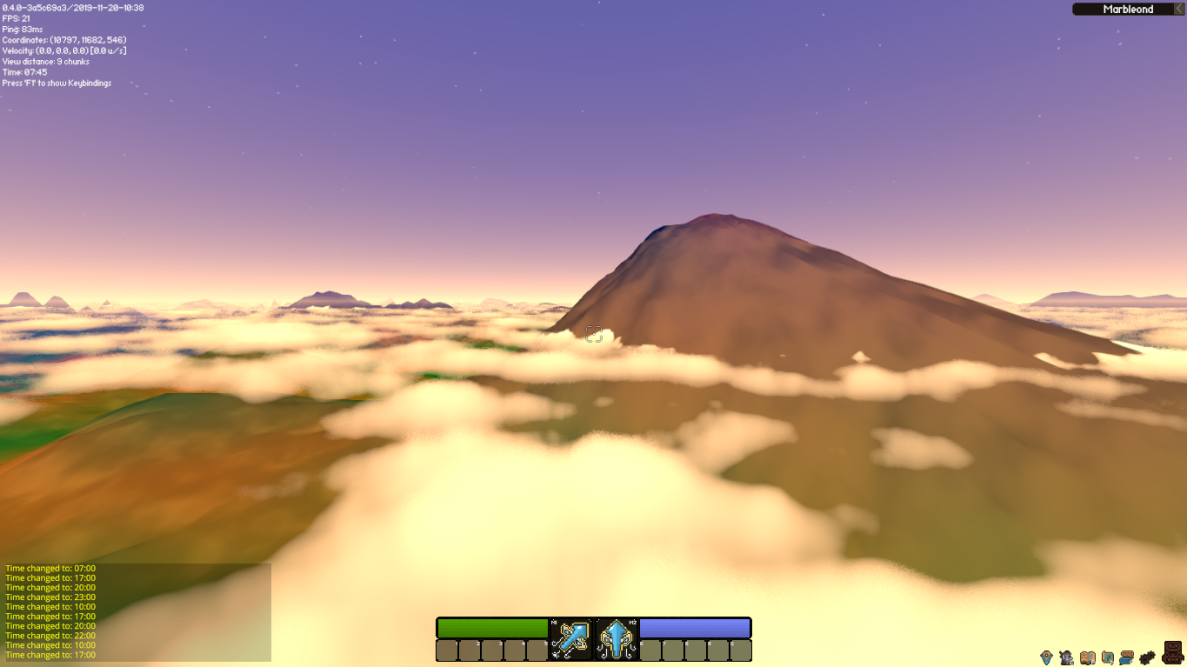

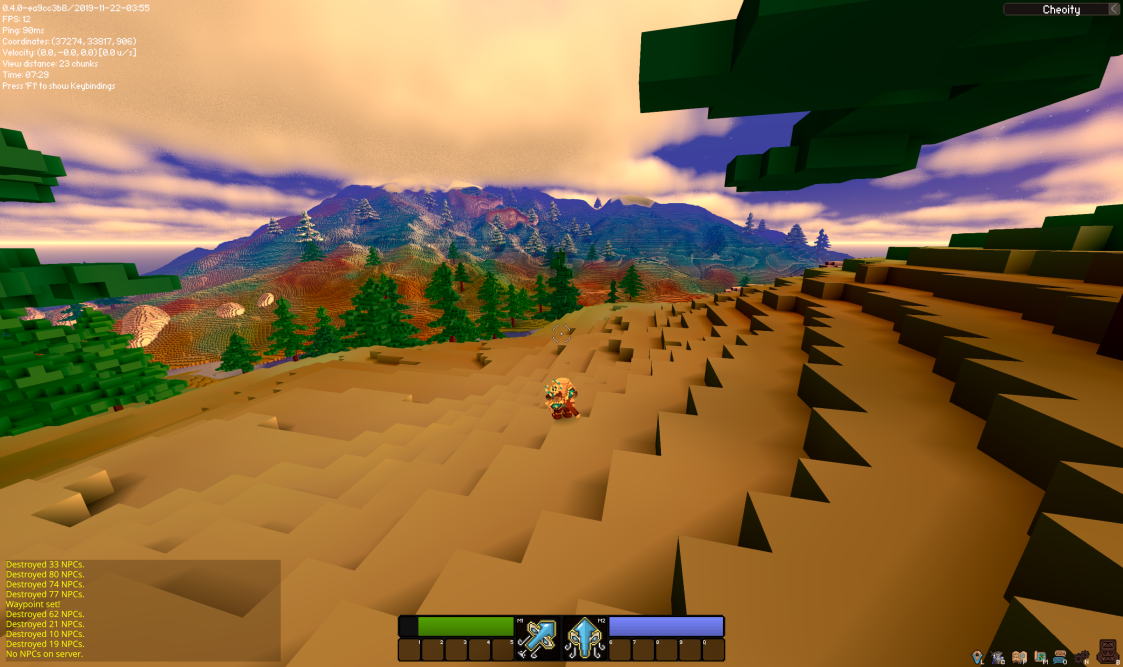

They were able to successfully reproduce things that evoked the feelings of a lot of terrain. Shattered hills, some kinds of ridged mountains, and so on. But never river networks, glaciation, or other processes that evolve in a more "global" way. Even though they sometimes produce fractal-like patterns, they don't do so randomly. Mountain above the clouds

People had the idea to just model the physical processes of things like water flow directly a long time ago. I think the first paper on computationally simulating hydraulic erosion came out in 1989. However, most of these early algorithms were "explicit", meaning that each new step relied exclusively on the values of the previous step. This made computing iterations much faster and simpler, and easy to parallelize. This is because each grid can operate in isolation for each round, and then just look at the effects of a previous round.

However, the downside is that explicit numerical methods do not converge to the same solution if you make the time step large enough Each of them has a certain range of time steps where they are "stable" and this varies by algorithm. If you're applying lots of different methods like this (as you often do for things like erosion), you are limited by the shortest convergence time scale of any of the methods In practice, this time scale is sometimes measured in years, or even days. While we need to simulate erosion over millions of years to get realistic looking landscapes.

The more recent innovations that have allowed these techniques to scale to large areas and time periods have thus been in finding clever implicit algorithms for solving these problems. In each iteration, an implicit algorithm computes values for all the cells "at once". This is done by solving partial differential equations, either exactly or using numerical methods with guaranteed convergence rates per iteration. The downside is that these equations are much more complex, and often require global information and ordering of the solution that makes them difficult to parallelize.

The upside is that a fully implicit method's convergence is not dependent on the time scale. This means that you can set it to any scale you want, so it will never be a bottleneck to your erosion algorithm.

Our fluvial erosion algorithm is a mixture of the two. First, we explicitly compute a river drainage network at a discrete-time point, and we only consider a single path from node to node rather than potential water flow from all paths.

Second, we implicitly compute the differential equation that predicts the effect of shear stress on the land elevations along that flow. Shear stress is the pushing effect that fluids have normal to their direction of flow. This allows for far larger time steps than we could use otherwise while guaranteeing, if not complete convergence, then at least something very close to it. A river at the bottom of a valley

Fluvial erosion is the process people are familiar with where water weathers the rock it flows over, eventually forcing it down and producing deep gouges. It gets stronger the higher its volume per time, which we approximate with the area flowing into the cell. This is one reason we compute a drainage network explicitly; the other is to figure out a single slope we can use in the equation.

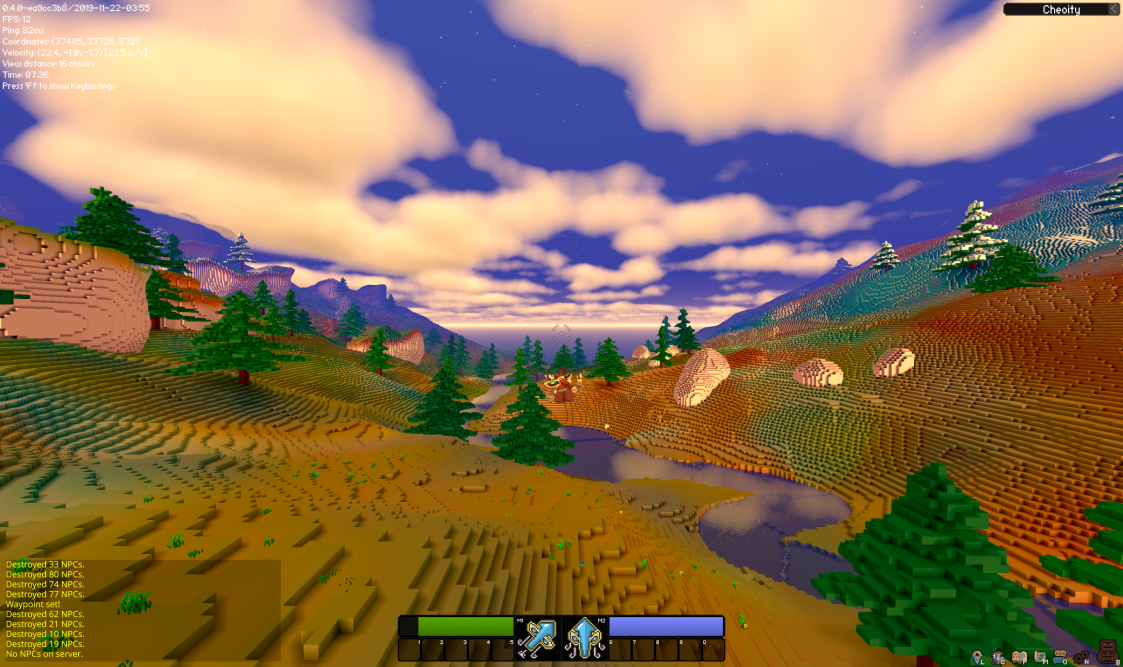

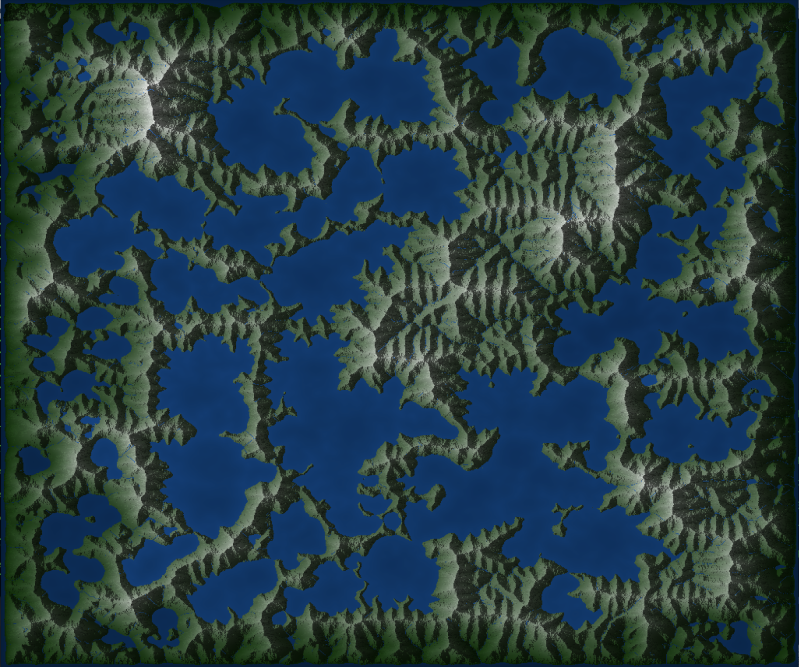

We currently combine this with three other algorithms. The first is tectonic uplift. This is relevant over large timescales. On land, at least some parts (not sure if all), there are areas where tectonic processes are causing more material to be released and thus rising the land above them. This allows mountains to develop out of even formerly flat ground and is a large advantage to us over other erosion algorithms that eventually tend to make all land flat. Tectonic uplift map

The second is thermal erosion, which reflects the tendency of rock to "slide" when above a certain angle. This is known as its talus angle, also called its angle of repose. It is dependent on the rock type and relates to the steepness that the rock grains can be heaped at before they start to slide down.

This corrects the tendency that stream power has to create extremely steep slopes, by breaking down the rock when it gets too steep, and has a large effect on the final elevation and overall map shape. It also has a nice side effect of limiting overall altitude in the presence of uplift. I think this is distinct from "mountain height" as mentioned in the paper, which I believe refers to how high a particular ridge can get before depositing into a basin; but I'm not sure.

The third, just added on my branch, is hillslope diffusion. This reflects the tendency of land to "slump" into each other, even below its angle of repose, and is a catchall for the effects of lots of different processes (e.g. wind). This equation is fully implicit, meaning it converges for every time scale no matter what, so it is pretty easy to add on as a step at the end. It is responsible for effects like making hills convex, beach slopes gentle, filling in small depressions, and creating new lakes (e.g. "oxbow" lakes) by blocking rivers with sediment.

We still use noise to influence uplift rates at each point, compose an initial continent shape, and control parameters to the erosion equations (such as rock strength and diffusion rate). We also still use noise heavily in the local generation of features, and for things like deciding on humidity and temperature maps; however, these things are also weighted by other factors (like altitude and flux). Over time, we hope to decrease the role of noise as we simulate more processes. Mountains off in the distance

There are many more things left to simulate, but so far this has given Veloren very distinctive and realistic-feeling worldgen compared to a lot of procedurally generated worlds, especially those which render things at a fine enough scale that you can play in them in 3D. Just having rivers and lakes guaranteed to actually flow downhill and connect up globally makes a huge difference in feel, as does having ridges in mountains and gorged valleys.

With hillslope diffusion, we also have features like oxbow lakes and islands built up out of sediment (smoother than regular islands). As we add more processes, we will get more diverse terrain and more biomes, but we could also get that with hardcoded biome types or noise-based approaches.

The use of physical processes, however, results in terrain that is much more interesting and diverse by comparison. This is because it allows for the interaction of all these effects. It also means that the interesting terrain will be cohesive with its environment, which is often a stumbling block for biome-based or noise-based generation. Your shattered hills may look great, but where do you put them and why are they there? The new loading screen by @Pfau. See you next week!